Bringing the Art of Imperial Craftsmanship into the Present: The One-and-Only “Suiun Carving” Woven by Hand

- Wood & wood products manufacturing

- Connecting with People

- Japanese Traditional Technology

- Creative

Shiga

“Suiun Carving,” a traditional craft passed down for over 70 years in Kaminyu, Maibara City, Shiga Prefecture, traces its origins to 1935, when the first-generation Suiun opened a carving workshop under this name. Known for its realistic and deeply three-dimensional carving techniques, Suiun Carving is a form of traditional craftsmanship with a distinctive style. Its scope spans a wide range of objects, including shrines, temples, festival floats such as danjiri and dashi, portable shrines (mikoshi), Buddhist altars, transoms, and even decorative pieces like the Seven Lucky Gods and Buddhist statues placed in alcoves (tokonoma).

This tradition and technique have been faithfully passed down to the second and third generations, who continue to infuse their works with relevance to the times while cherishing its heritage. The Intricacy and warmth of hand-carving—impossible to replicate with machines—continue to captivate all who encounter these works.

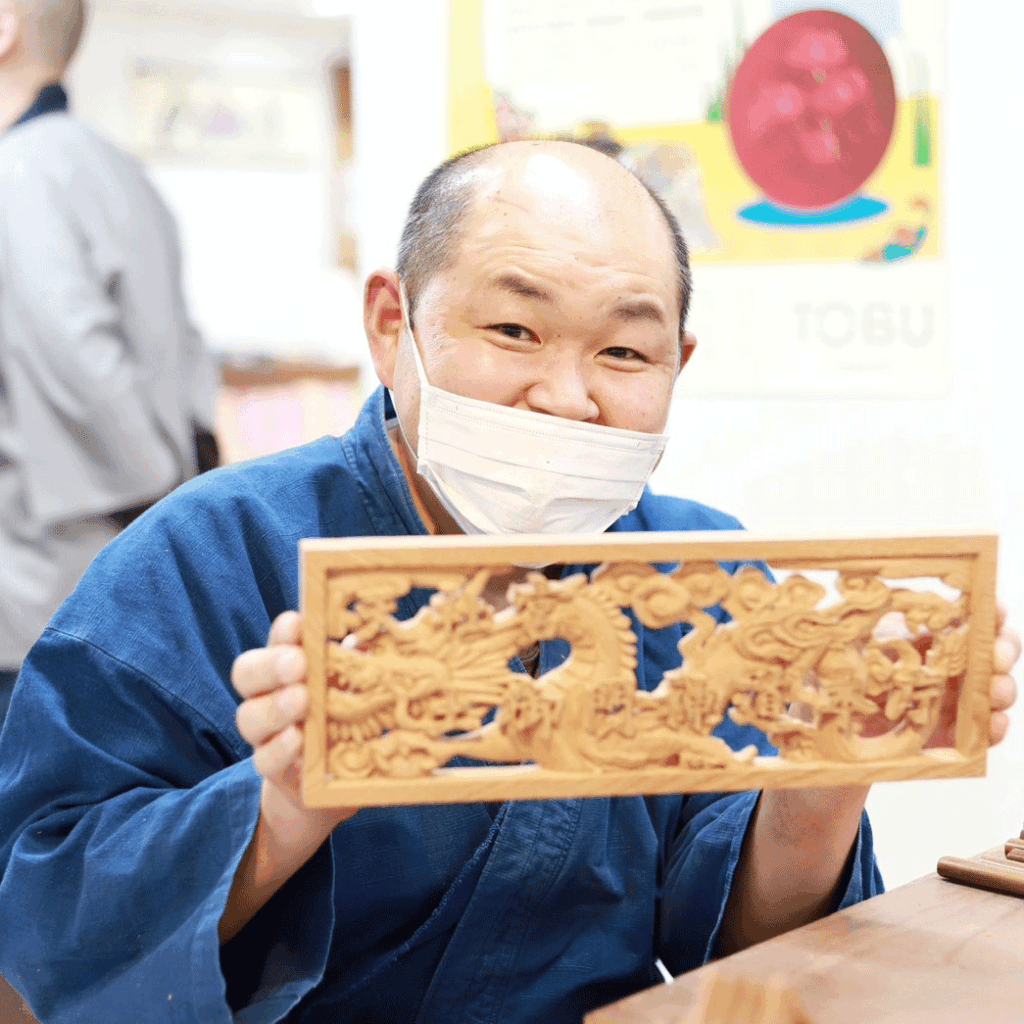

In this article, we speak with Kazushige Ijiri, the third-generation head of Ijiri Chokokusho, who has inherited the legacy of Suiun Carving, to learn about his path to taking over the family business, his mindset as a craftsman, and his vision for the future.

PROTAGONIST

Kazushige Ijiri3rd Generation

Anything Can Be Made: Custom-Made Carvings

In 1935, the first-generation Suiun established a carving workshop under the name “Suiun Carving” in Kaminyu, Maibara City. Kaminyu has long been known as a “village of artisans,” a region renowned for its thriving Buddhist altar-making tradition. At the time, Suiun’s father worked as a charcoal burner in the mountains—a job that was both physically demanding and grueling. As a result, Suiun chose not to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Instead, he became an apprentice to a master carver named Mori, who was known for dynamic carving in the Ueda school style. While assisting Mori, Suiun honed his skills. Entering the world of carving at the age of 14, he had, by the age of 24, already begun training apprentices of his own—a testament to the remarkable skill that had earned him widespread recognition.

Later, Suiun’s craftsmanship garnered further acclaim when he was commissioned to create an offering for the Crown Prince (now the reigning Emperor of Japan). Since its founding, the tradition of Kaminyu carving has been faithfully passed down for over 70 years.

Today, Ijiri Chokokusho produces a wide range of carved works, from shrine and temple sculptures and danjiri (festival floats) to Buddhist altars, transoms, nameplates and shop signs that serve as the face of homes and businesses, and even accessories. The workshop is especially skilled in custom-made creations.

“We carefully select high-quality wood such as zelkova, Japanese cypress, camphor, asunaro, magnolia, cherry, and Japanese cedar (including Yakusugi cedar). We also use Biwako-zai, timber thinned by forestry cooperatives in Shiga Prefecture. By making accessories from Biwako-zai, we hope to promote the value of Shiga-grown wood as a branded material.”

The ability to craft virtually anything is one of Ijiri Chokokusho’s greatest strengths. They also devote significant effort to creating decorative pieces for restaurants, having produced ceiling carvings for a sushi restaurant in Hiroo, Tokyo, and transoms and signage for the French restaurant epice in Kyoto. Their dream is to one day create monumental works for the entrances and lobbies of hotels overseas.

I had no choice but to figure out what was necessary on my own.

Ijiri recalls that from a young age, he enjoyed drawing and creating things. He grew up surrounded by the daily sounds of chisels echoing through the family workshop—a place where traditional carving tools were constantly at work. He says it was that environment, filled with the rhythmic sound of craftsmanship, that naturally led him down the path of carving.

“My father, the second-generation head, originally dreamed of becoming a professional golfer. But he gave up that dream and chose the path of a craftsman. He used to tell me, ‘Do what you love. You don’t have to think about carving.’”

Ijiri learned techniques and knowledge from his grandfather and the workshop’s apprentices while growing up in a setting where he was always face-to-face with the world of carving. Upon graduating from Meijo University’s Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, he made the decision to take over the family business. Becoming a craftsman felt like the natural course for him. Since he believed that the skills of his grandfather—the founder—were unmatched, he never considered training at another studio.

“My grandfather was truly strict and intimidating. I couldn’t understand it at the time, but now I realize that each of his words has become the very foundation of who I am today.”

No two carved works are ever the same. It was normal to go from making a transom to a Buddhist altar, or from a large piece to a delicate, intricate one. As the work changed, so did the chisels that were needed. Because the studio took on all kinds of commissions, mastering each technique was a challenge.

“They say it takes three years to master chisels and sharpening, and ten years to become a full-fledged craftsman. But I always want to aim higher. That’s why I believe the journey of training lasts a lifetime.”

Although Ijiri had resolved to pursue the path of a craftsman, everything changed once he began working as a sole proprietor. With fewer temples being built and the Buddhist altar industry in decline, the times grew harsher.

“Until then, I had a stable job and received a regular salary—it was only natural to have work. But after I started my own business, the number of jobs dropped dramatically. So I threw myself into new challenges I had never tried before, like participating in department store events and collaborating with designers. I actively joined seminars and union activities, and I even studied marketing. In this changing era, I had no choice but to figure out what was necessary on my own.

The turning point was the opportunity to create the signboard for NGK (Namba Grand Kagetsu). When that job came my way, I saw it as a chance.”

At the time, people around him expressed doubts, asking, “Can you really pull this off?” But those concerns only fueled Ijiri’s determination. The NGK signboard project, carried out by a team of three while continuing their regular work, took six months to complete. It proved to be a major milestone, one that significantly raised the profile of Ijiri Chokokusho.

Each piece is meticulously crafted by the hands of skilled artisans.

During his early years of training, Ijiri was assigned only the task of shaving surfaces cleanly—a repetitive process that eventually led to tendinitis. He recalls that carving danjiri was particularly challenging due to the intricate work required on extremely hard zelkova wood.

“At first, I honestly thought I couldn’t do it. But as I kept carving, I gradually started to understand. When you do it every day, carving begins to feel like drawing. I believe anyone can do it, really. Right now, I’d say I’m half craftsman, half salesman.”

Ijiri emphasizes that the initial rough-carving stage, known as arabori, is the most critical part of the carving process.

“The overall shape is determined during arabori, so it’s the most important phase. If it’s off at that stage, there’s no way to fix it during the finishing process. For example, in the beckoning cat I’m currently working on, the legs are still in the rough-carving stage, and it’s essential to shape them properly at this point.

On the other hand, the final step—called chōshiage or super-finishing—comes with its own difficulty. Using carving knives to polish the surface to a smooth finish requires extreme precision and care. If you rush through it, the quality of the final piece drops significantly.”

At Ijiri Chokokusho, every piece is completed through careful, hands-on work, from rough carving to the final polish. The studio specializes in dynamic carvings such as dragons and guardian lions, and offers fully custom-made works in all sizes. There are few workshops that provide completely bespoke carvings—this is one of Ijiri Chokokusho’s unique strengths. The warmth and detail of its hand-carved work are qualities no machine can ever replicate.

I want to promote Maibara as a town of craftsmanship

The vision of Ijiri Chokokusho is to pass down traditional carving techniques to the next generation while creating new works that meet the demands of the times, thereby spreading the appeal of woodcarving culture. As part of this effort, the workshop launched a carving experience group called the Kaminyu Woodpeckers in 2020. Initially, they planned to collaborate with a travel agency that offered tours for foreign visitors, incorporating the carving experience as part of the itinerary. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic forced a temporary halt to these activities, prompting a shift toward offering programs for Japanese participants. Recently, however, they have received applications from people of American and Dutch nationality.

“People from overseas also show a great interest in wood. Some even work as hobbyist carpenters and are quite skilled with tools. It’s truly rewarding to see them enjoy the experience of carving.”

Currently, Ijiri has no formal apprentices, but he has conducted short-term instruction in the past. One woman he mentored for a month went on to leave her corporate job and establish herself as an independent carver in Wakayama, where she continues to enjoy her work to this day.

“It makes me happy to see that she’s still enjoying it. These days, learning under a master alone isn’t enough to sell your work. But with tools like social media, it’s now possible to promote your own creations and find your own market. Wood can take on many forms, so I think if young people approach it with flexible, fresh perspectives, there’s a lot they can achieve.”

Ijiri hopes that more people will come to appreciate the beauty of woodcarving.

“I’d love for people from overseas to visit the workshop as well. I want to enhance our international e-commerce site and promote Maibara as a town of craftsmanship that draws attention from around the world. If the appeal of woodcarving spreads, and more people start saying they want to live in Maibara—and one day I meet a future successor because of that—that would be the best outcome. Just imagining that kind of future excites me.”

At Ijiri Chokokusho, each piece is one-of-a-kind, crafted based on customer orders. Every creation carries the warmth of handwork and the passion of the artisan. These works resonate deeply with those who see them, radiating the dynamic beauty that only woodcarving can offer.

INFORMATION

Ijiri Woodcarving Studio

If you're looking for wooden carvings, leave it to Ijiri Woodcarving Studio in Shiga. We create a variety of items such as nameplates for homes, store signs, carvings for festival floats (danjiri), accessories, small items, and custom-made woodcarvings. We carefully select the wood most suitable for each piece and, using skills honed over the years, our artisans hand-carve each work to closely match your vision. Our pieces offer a level of detail, originality, and warmth that machine carving simply cannot replicate. Feel free to consult us about the intended use, design, and budget for commemorative items, gifts, or keepsakes.

- Founded in

- 1935

- No. of employees

- -

- Website

- https://ijiri-choukokusho.com/

- Writer:

- GOOD JOB STORY 編集部