A Furniture Craftsman Who Breathes New Life into Scrap Materials: Turning “The World’s Most Expensive Furniture” into a Global Brand

- Wood & wood products manufacturing

- SDGs & Sustainability

- Unique Products & Services

- Efforts for the Community

- Considering Earth's Resources

Osaka

Palette House Japan is a company engaged in the creation of legged furniture—such as tables and chairs—and box furniture—such as bookshelves and cupboards—as well as spatial coordination, including store design and comprehensive production. What sets the company apart is its unique use of scrap wood as its primary material. In particular, it dismantles wooden pallets used in imports for transporting goods and repurposes them into furniture.

As Japan is a major importing country, shipments frequently arrive with pallets designed for forklifts. These inexpensive, mixed-wood pallets—commonly referred to as “one-way” pallets—are often discarded without reuse. It is said that the total amount of such waste reaches as much as 900,000 tons annually.

Palette House Japan collects and dismantles these discarded materials, breathing new life into them as furniture. We spoke with Hiroshi Omachi, the representative of this small factory in Osaka City.

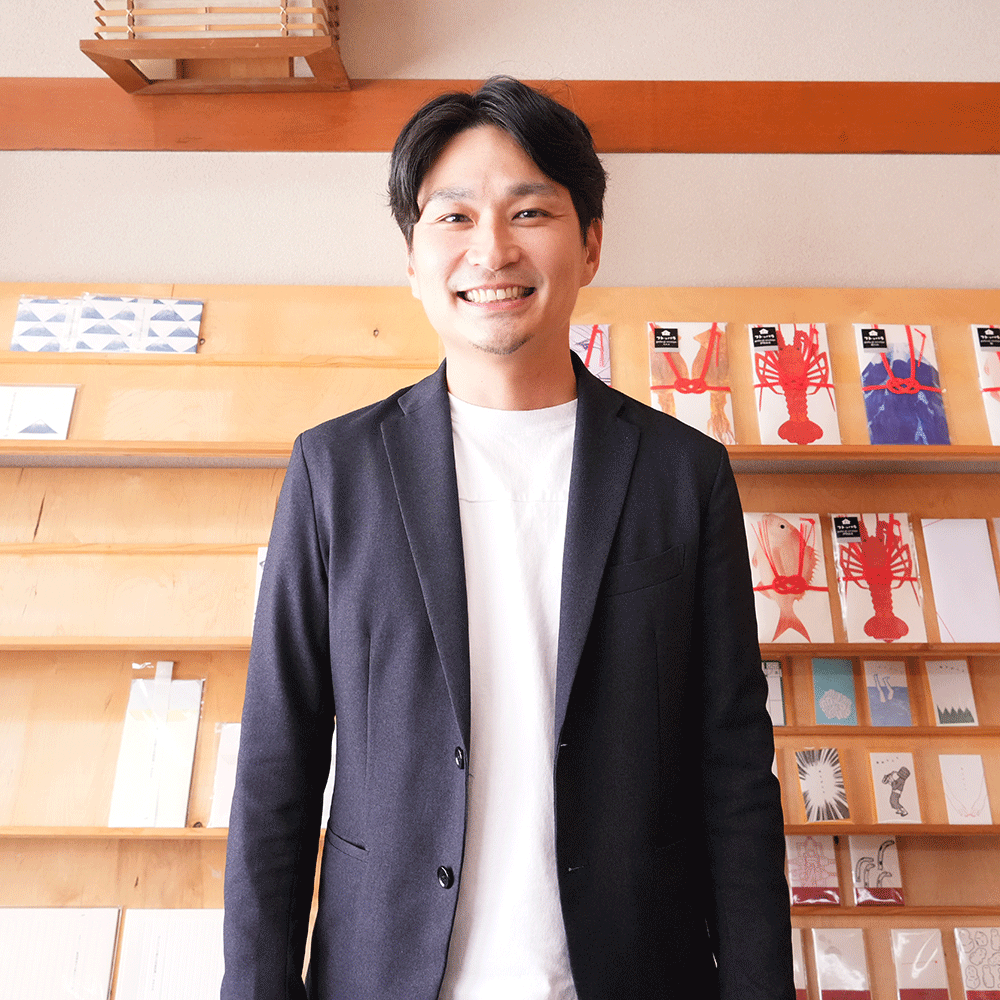

PROTAGONIST

Hiroshi OmachiPresident and CEO

Earning Customer Trust Through a “Tip-Based Life”

Palette House Japan collects wooden pallets before they are discarded as industrial waste, then dismantles, washes, and dries them through a careful process to reincarnate them into furniture such as tables and bookshelves.

“Making tables from scrap wood probably makes them the most expensive furniture in the world,” Omachi laughs. “The processes of collecting, dismantling, washing, and drying—none of which typical furniture manufacturers do—incur high labor costs, making it difficult to turn a profit. But that’s exactly why creating a global brand with expensive furniture made from discarded materials has meaning.”

While new materials do not need to be purchased, each piece of scrap wood requires individual restoration, involving both technical skill and time. This is because each piece of wood has its own unique character, and no two are ever the same.

“I want to return once-living trees to society. If no one else is going to do it, I will. Transforming the scrap wood I encounter into vintage-style furniture feels like an adventure—it’s thrilling.”

The core philosophy of Palette House Japan is “Waste Wood First.” Following that comes the Earth (the environment), and only then the customer. Although customers are the ones paying money, Omachi considers them not mere buyers, but supporters of the mission—true patrons.

This stems from his desire for people to feel not just the appeal of the furniture as a product, but to share in the reality of the revival of discarded materials, now reborn in tangible form. “Actually, these reborn scraps also function as furniture,” he says with a smile. He hopes customers will care for the pieces as they would a family member. This attitude—valuing emotion more than money—is what earns the trust of his customers.

Another of Omachi’s compelling qualities is his deep affection not only for waste wood but for wood itself.

“I believe that scrap wood is still alive. That’s why I want to help it be reborn and returned to society again. It’s a bit like rescuing stray cats or dogs and finding them new owners. I want customers to know, ‘This is reborn scrap wood—please treat it like family.’ I want them to feel it’s not just an object, but something alive.”

This belief led to the creation of a groundbreaking system that ensures the furniture is never discarded again. Under this system, Palette House Japan offers to buy back the furniture at half price after 10 years, and at full price after 20 years.

“If we buy it back in full after 20 years, we believe the customer will see it as something they could never throw away. And when we buy it back, we resell it at double the price. A ¥200,000 piece becomes ¥400,000 after 20 years. That ¥400,000 piece, in another 20 years, will be bought for ¥400,000 and sold for ¥800,000. This proves that ‘the older, the more valuable’—that’s what vintage furniture is about. The older it gets, the more value the manufacturer places on it, so no one will ever throw it away. That’s how furniture can live forever.”

Such a system cannot be found anywhere else in the world. “Furniture made from waste wood with a 100-year maintenance guarantee”—this is a reflection of the confidence behind Palette House Japan.

While always keeping customers in mind, Omachi remains steadfast in his slogan:

“From Waste Wood to a Global Interior Brand!”

By taking the initiative to raise the value of vintage furniture themselves, they embody a philosophy that will never waver.

How a Fight with the Boss Led to a Furniture Store That Doesn’t Sell

Hiroshi Omachi once aspired to become a comedian. During his adolescence, being overweight became a source of insecurity. By playing the role of the “funny fat guy,” he gained popularity, which in turn fueled his dream of becoming a comedian. However, things did not go so smoothly. After graduating from university and going through various twists and turns, he became a company employee and was on the verge of giving up on comedy. But by a stroke of luck, he was introduced to Toshio Sakata—also known as “Aho no Sakata” from Yoshimoto Kogyo, Japan’s leading comedy and entertainment company known for its manzai duos.—who happened to be looking for a driver. Omachi became his driver and apprentice. It was the spring of his 24th year.

Despite living in extreme poverty, he endured two years of strict training. At the age of 26, he debuted as “Right Sakata,” the boke (funny man) in the manzai duo “Limelight.”

He drew attention for his unconventional comedic style. Jimmy Ōnishi, a senior comedian by two years, told him, “You’re even more of a fool than I am,” while Shinsuke Shimada said, “You’re the only one standing in the batter’s box holding an umbrella!” Although his time as a comedian lasted only five years, he won several awards and was even called the “next Downtown” at one point. However, due to differences in comedic style, the duo disbanded. Afterward, he spent a year traveling through Europe and the United States, ultimately arriving in New York to study global entertainment. Ironically, that experience led him to lose confidence in himself.

“There were too many incredible entertainers overseas. I lost the confidence that I was the best. I also ran out of money and felt my limitations. After returning to Japan, I continued working solo as a radio reporter, but I also started a part-time job at a friend’s furniture store to make ends meet. Eventually, I started to feel that customer service and sales might suit me better than being a comedian.”

As a part-timer, he would greet customers with, “You shouldn’t buy furniture! Japan is too small compared to overseas.” Though customers were initially surprised, they gradually began to trust him, saying, “That blond guy doesn’t try to force a sale.” He became known as “the guy from the furniture store who doesn’t sell” and ironically became the top salesperson. Naturally, this often put him at odds with the store’s president, who would ask, “Are you on the store’s side or the customer’s?”

“Whenever that happened, I immediately replied, ‘Of course I’m on the customer’s side!’ The angry president once told me, ‘You’re just a comedian, that’s why you can say things like that! Comedians can’t run a business!’ But what’s wrong with being on the customer’s side? While everyone else grabs a short bat and runs to first base, I stand in the batter’s box with an umbrella and run to third base. I was always thinking differently from the president. I was satisfied when people called me a fool—because I’m a disciple of Sakata the Fool.”

Then he wondered, what kind of shop would a comedian-run furniture store be? Of course, what he wanted to create was a “funny furniture store.” That idea eventually led to the founding of “Unko-chan’s Furniture Shop” in 2004.

Taking On the Challenge of Scrap Wood Furniture That No One Else Dares to Make

After going independent, Omachi launched a furniture shop called “Unko-chan’s Furniture Shop.” It was a name that no “sensible person” could have imagined. The furniture industry was stunned. Even the delivery trucks bore messages like “Don’t underestimate Unko-chan!”, serving as Omachi’s playful yet provocative message to the industry.

At first, people in the furniture business dismissed it, saying, “That silly store, selling second-rate products, will go under in no time.” However, “Unko-chan’s Furniture Shop” began to gain attention through word of mouth, even in the pre-social media era, and sales steadily increased. The later boom of the “Unko Drill” educational books in Japan came 13 years after that, making it no exaggeration to say Omachi was a pioneer of the keyword.

The shop offered a theme park-like space, unlike the dull and ordinary furniture stores that had come before. On weekends, Omachi would dress up as an “Unko Alien” and play with children, which became immensely popular, leading to a rush of TV coverage. In just a few years, what was once considered “gimmicky” had become widely accepted. As customers flocked to the store and money came in without effort, there was no longer a need for aggressive gimmicks. All his time was spent dealing with customers, and he stopped coming up with new ideas. Eventually, he began to feel, “I don’t know what I want to do anymore. I’ve become just another furniture store.” As the originality faded, “Unko-chan’s Furniture Shop” began a slow decline.

In the seventh year since founding, on March 11, 2011, a turning point arrived.

“I saw homes washed away by the Great East Japan Earthquake, with shattered houses and furniture drifting ashore. It made me realize something again. Furniture is not just a tool—things like dining tables are like family members that people touch every day. That’s why I thought, maybe I could make furniture from those piles of rubble. But I couldn’t build furniture myself. Even furniture manufacturers told me it was impossible. Was there really nothing I could do? That frustration became the biggest turning point for me.”

Three years later, he learned about the vast number of wooden pallets being discarded.

Omachi had a flash of inspiration: “Maybe I could turn these pallets, which are normally burned as garbage, into vintage-style furniture.”

“And at that moment,” he said, “I heard a voice from the god of wood speaking in Kansai dialect: ‘You’re the one who’s gonna save this scrap wood!’”

Normally, wooden pallets cannot be incinerated as regular waste. They are treated as industrial waste and disposed of accordingly. In the eyes of society, they no longer have a purpose as wood. But Omachi believed otherwise—they were still alive and still had work they could do.

In the ninth year since launching “Unko-chan’s Furniture Shop,” Omachi decided to embark on a new adventure. He resolved to return abandoned scrap materials to society. It was his way of avenging the Tōhoku disaster.

“If no one else will do it, then I’ll build a scrap wood furniture company myself!”

Using the salary he had earned from “Unko-chan’s Furniture Shop,” he handed over the business he had built. Then in 2014, he founded “Palette House Japan,” a furniture manufacturer dedicated to bringing discarded wood back into society.

2,780 Yen Left — A Vision of the “God of Wood” at the Brink of Bankruptcy

Making furniture from scrap wood requires three times the effort of conventional furniture production. The process involves collection, transportation, dismantling, washing, and drying. Labor costs are enormous. It is a business model that anyone can see is unlikely to be profitable. In the 11 years since starting, the company turned a profit only twice. Omachi reportedly spent 60 million yen of his own money. Rent, salaries, purchasing trucks for material transport—all expenses were covered out of pocket. Naturally, as the president, he could not afford to pay himself a salary.

“At the end of the year, the company’s bank balance had dropped to just 2,780 yen. Most people would have given up long before that, I think (laughs). But I had no intention of quitting. Even as I thought, ‘We might not last another three months,’ I had this strange conviction: ‘The god of wood will take care of things.’”

Then, on January 15, right after the new year, a miracle began. An OEM catalog produced with a partner manufacturer was completed. The quality of the catalog sparked cheers of excitement. The manufacturer even made a 1 million yen advance payment for display products. Moreover, a company acquaintance who saw the catalog requested the construction of a showroom. When Omachi explained the lack of funds, they immediately transferred 5 million yen in advance. The god of wood had stripped him of everything—but in the end, did not abandon him.

From that point forward, major companies such as Umeda EST Food Hall, Yokohama Bayside Food Hall, Hanshin and Hankyu Department Stores, NTT West, Nikken Sekkei, and Panasonic began adopting his products. The comeback story had begun.

Having overcome the brink of bankruptcy, Palette House Japan is now a leading player in the SDGs movement, aiming to become a global brand of scrap-wood furniture. Not just globally available, but in the high-end market. In other words, it is the “Lamborghini of scrap wood.”

The company has introduced a string of industry-first ideas, such as “tabletop replacements without waste,” “subscription-based startup support,” and “free products after 20 years of use.” With his trademark bold thinking that no one else dares attempt, Omachi continues to establish a strong presence as a Japanese SDGs manufacturer on the world stage.

A man who stands in the batter’s box holding an umbrella—that’s Hiroshi Omachi. Today, at 65, he’s better known as the “Dancing Scrapwood Uncle,” singing, dancing, and charming audiences across social media. (laughs)

Aiming to Become a Sophisticated Global Company Where Scrap Wood Takes Center Stage

After achieving success and experiencing a major turning point with “Unko-chan’s Furniture Shop,” Hiroshi Omachi made the decision to embark on his next challenge. That challenge was to develop and expand furniture production using scrap wood on a global scale. He was convinced that furniture made from scrap wood held possibilities far beyond simple recycling.

Omachi has a clear goal: to build a global brand using discarded wood.

“I have a lot of dreams,” he says. “For example, getting Lady Gaga to wear clothing made from scrap wood, appearing on the program Gaia no Yoake, being featured in the magazine Shoten Kenchiku, or having our products used by international companies. Ultimately, I hope our furniture will be embraced in environmentally conscious regions like Europe, America, and the Nordic countries. If possible, I’d love to see the day when the world calls us first, and I can flash a smug smile and say, ‘Took you long enough.’ (laughs)

In the manufacturing industry, the movement to make effective use of scrap wood is still in its infancy. Omachi believes that regional cooperation is essential to realizing his vision of “creating a global brand from global scrap.” He also expresses confidence in the potential reuse of timber following the 2025 Osaka-Kansai Expo. That confidence is rooted in 12 years of experience in returning discarded wood to society.

“In the end, I think the best compliment would be hearing the neighbors say, ‘They do good work—even if the pay is low.’ We’re not the main characters here—the real stars are the scrap materials. The role of Palette House Japan is to support those abandoned pieces of wood so they can be reborn and live a long life with a new family.” The “Scrap Wood Old Man,” now 65, smiled brightly and said he’s just a servant of the god of wood.

While remaining deeply rooted in the local community, Omachi envisions building a refined company that operates on a global stage. In Japan, it is often the case that a company’s value is recognized abroad before it gains recognition domestically. Given its commitment to valuing wood, Palette House Japan’s approach may well be viewed overseas as a meaningful response to pressing social issues.

Omachi expresses strong ambition, saying, “By strengthening ties with local communities and building a sustainable model for utilizing scrap materials, I want to establish our position as a truly global brand.”

INFORMATION

Pallet House Japan

PALLET HOUSE JAPAN was founded on March 11, 2014.

Young creators, craftsmen, and designers from the Kansai region gathered in a small factory in Osaka City to transform discarded wooden pallets and old scaffolding materials from Kansai’s industries into vintage-style designer furniture, using unique ideas, bold designs, and authentic furniture-making techniques.

We also provide total design services for interior spaces centered around this furniture.

Aiming to become a world-class interior brand under the motto:

"Doing what no one does, and what no one can do."

Recently, our concept and eco-friendly designs have gained a strong reputation, not only among general consumers but also in various fields such as restaurants, apparel shops, offices, and the renovation of second-hand homes.

We offer comprehensive interior production — from shop and interior design, furniture sales, and original furniture, to complete construction.

- Founded in

- 2014

- Website

- https://www.pallet-house.jp/

- Writer:

- GOOD JOB STORY 編集部